Bull shark

The bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas), or Zambezi shark, is a species of shark of the genus Carcharhinus.

| Bull shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Binomial name | |

| Carcharhinus leucas | |

| |

| Range of the Bull shark | |

The shark grows to a maximum length of 11.5 feet (3.5 metres), but is usually 7.3-7.8 feet (2.2-2.3 metres) long. It is found in tropical and subtropical coastal waters worldwide, as well as river systems and freshwater lakes.

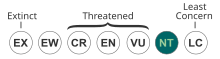

This species is listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN and is considered to be the third most dangerous shark in the world.

Description

changeBull sharks have a very sturdy body, and have a blunt, rounded snout, giving the Bull shark its name. The first dorsal fin is large and widely triangular with a pointed tip. The second dorsal fin is noticeably smaller. The pectoral fins are also large, and have sharp tips. Bull sharks have quite small eyes as compared to other carcharhinid sharks, which might mean that vision is not a very important hunting tool for this species which is usually found in muddy waters. Bull sharks are usually pale to dark grey above, and their undersides are white. In young Bull sharks, the fins have black tips which turn to a dusky colour as they grow. The teeth of the upper jaw are wide, triangular, and heavily jagged. The teeth of the lower jaw have a wide base, and are narrow, triangular, and are finely jagged. The front teeth are raised and are nearly symmetrical, while the back teeth are more slanted in shape. WSG

The maximum weight is over 500 pounds (230 kg). The size at birth is around 29 inches (75 cm). Females are larger than males, reaching a length of around 7.8 feet (2.4 metres) as adults, and weighing around 285 pounds (130 kg). This is the result of a longer lifespan of about 16 years, compared to 12 years for males. Males reach a length of around 7.3 feet (2.2 metres), and weigh 209 pounds (95 kg). The growth rates calculated from captive Bull sharks were estimated to be about 11 inches (28 cm) per year in the first years of life, slowing to half that rate after about 4 years of age.[1]

Habitat

changeThe Bull shark is found in tropical and subtropical coastal waters worldwide as well as in many river systems and some freshwater lakes. They have been reported 3700 km (2220 miles) up the Amazon River in Peru, and over 3000 km (1800 miles) up the Mississippi River in Illinois. A group of Bull sharks found in Lake Nicaragua (Central America) was once thought to be landlocked, but they found access to the ocean through rivers and estuaries. In the western Atlantic Bull sharks migrate north along the coast of the U.S during summer, swimming as far north as Massachusetts, and then return to tropical climates when the coastal waters cool. The Bull shark likes to live in shallow coastal waters less than 100 feet deep (30 metres), but ranges from 3–450 feet deep (1–135 metres). It commonly enters estuaries, bays, harbours, lagoons, and river mouths. It is the only known shark species which is found in freshwater, and can spend long periods of time in such environments. It is not likely that the Bull shark's entire life cycle is within a freshwater system, however. There is evidence that they can breed in freshwater, but not as regularly as they do in estuarine and marine habitats. Young Bull sharks enter estuaries with low salt contents and lagoons as readily as adults do, and use these shallow areas as nursery grounds. They can also live in waters with high salt contents; as high as 53 parts per thousand.[1]

Behaviour

changeEven though humans are not on their diet, bull sharks have been known to be very aggressive towards humans. This shark can be a danger to people since many people don't have the knowledge that Bull sharks can be found in rivers and freshwater. Almost all of the close to shore shark attacks on humans have been caused by this species. They are listed as the 3rd largest risk to humans when it comes to sharks. They are only behind the Great White Shark and the Tiger shark. They are very territorial and they will attack anything that gets into their environment and they feel is a risk. They have been known to bite horses and other animals that come to close to the water.[2]

Although the Bull shark has no real predators, young Bull sharks have been known to fall prey to Tiger sharks, Sandbar sharks, and even adult Bull sharks. Parasites, like Pandarus sinuatus and Perissopus dentatus, have been found in Bull sharks, and parasitize the body surface of this shark.[1]

Diet

changeThe Bull shark mainly feeds on bony fish and small sharks. In the western Atlantic they commonly feed on mullet, tarpon, catfish, menhaden, gar, snook, jacks, mackerel, snappers, and other schooling fish. They also regularly feed on stingrays and young sharks including small individuals of their own species in their inshore nursery habitats. Bull sharks are also been known to feed on sea turtles, dolphins, crabs, shrimp, sea birds, squid,[1] terrestrial mammals, echinoderms, and crustaceans.[2] Bull sharks often appear sluggish as they slowly swim along the bottom, but are quite quick and good at capturing smaller, agile prey, and are capable of burst speeds of over 11 mph (19 km/h).[1]

Bull sharks may spend many hours each day looking for food. They will eat heavily too when there is a large amount of food to be found. They mostly hunt on their own, but there have been observed times when a pair of Bull Sharks will hunt as a team.[2]

Reproduction

changeBull sharks are viviparous, meaning that they give live birth. The gestation period is about one year, usually during the summer months but sometimes in early autumn as well.[3] Bull sharks usually migrate to river mouths to mate and have their young.[2] Pups are about 60 cm (24 inches) long, and mothers give birth to 5 to 15 pups at a time. Coastal lagoons, river mouths, and estuaries with low salt contents are common nursery habitats.[3]

Bull sharks reach maturity depending on where they are. One study in the southern Gulf of Mexico found that the age of maturity was 10 years (7 feet) for females and 9–10 years (6.2-6.6 feet) for males. Another study in the northern Gulf of Mexico showed that the age of maturity was 7 feet (14–15 years) for males and 7.4 feet (18 years) for females.[1]

Other names

changeThe Bull shark gets its name from its sturdy appearance and aggressive nature. In French, the Bull shark is known as "requin bouledogue". In Spanish it is known as "tiburon sarda". It is known by many different names throughout its range including "Zambezi shark" and "Van Rooyen's shark" in Africa, "Ganges shark" (India), "Nicaragua shark" (Central America), and "Freshwater whaler", "Estuary whaler", and "Swan River whaler" in Australia. In English it is also known as the "Shovelnose shark", "Square-nose shark", "River shark", "Slipway grey shark", "Ground shark", and "Cub shark".[1]

Conservation

changeAlthough the Bull shark is rarely the target species of commercial fisheries, it is usually caught accidentally along with other catches. Since it is found inshore, it has been made a target for artisanal fisheries. The meat of the Bull shark is eaten by humans, the hide is used for leather, the fins are used in shark-fin soup and the liver is made into vitamin-rich oils. In certain areas, such as the Gulf of Mexico and South Africa, the Bull shark is also a popular game fish. The Bull shark’s inshore and freshwater habitat not only makes it an easier target of fisheries, but since these habitats are usually polluted and are targets to habitat modification, the Bull shark is in danger. The Bull shark is listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN [4]

Danger to humans

changeAccording to the International Shark Attack File (ISAF), Bull sharks are responsible for at least 69 unprovoked attacks on humans around the world, 17 of which have resulted in deaths. However, this species is likely to be responsible for many more attacks, and has been considered by many experts to be the most dangerous shark in the world. Because of its large size, its ability to enter freshwater, and the fact that it is found inshore, it might be more of a threat to humans than either the Great White Shark or the Tiger shark. Since the Bull shark is found in many Third World regions including Central America, Mexico, India, east and west Africa, the Middle East, southeast Asia, and south Pacific islands, attacks are often not reported. The Bull shark is also not as easily identifiable as the Great White or the Tiger shark, so it is likely to be responsible for a large percentage of attacks with unidentified culprits. The Bull shark has been considered to be the culprit in the infamous series of five shark attacks in New Jersey in 1916 which resulted in four deaths over a 12-day period. Three of these attacks happened in Matawan Creek, a shallow tidal river, only 40 feet (12 metres) across, 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from bay waters, and over 15 miles (24 km) from the open ocean; not a location where any other large shark species would likely be found. A 7.5 foot (2.25 metres) Great White was captured two days after the last attack, however, just 4 miles (6.4 km) from the mouth of Matawan Creek, and contained human remains in its stomach. A 9-foot (2.7 m) Bull shark was also captured a day later only 10 miles (16 km) from Matawan. This has been a topic of debate for many years, and there is evidence that points at both, the Bull shark and the Great White as the culprits.[1]

References

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 "FLMNH Ichthyology Department:Bull shark". flmnh.ufl.edu. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Bull shark-Animal Facts and Information". bioexpedition.com. 13 June 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Bull Shark Facts |Shark Breed Info |Types Of Sharks". the-shark-side-of-life.com. Archived from the original on 19 July 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ "Bull shark videos, photos, and facts-Carcharhinus leucas-ARKive". arkive.org. Archived from the original on 12 July 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2013.