California genocide

During the California genocide (1846-1873), government agents, private militias, and ordinary people killed thousands of indigenous people in California. These were systematic killings: people organized them and meant to commit them.

| California genocide | |

|---|---|

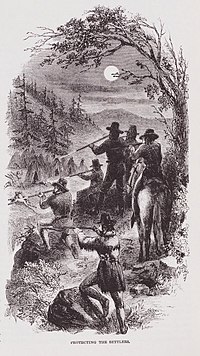

"Protecting The Settlers", illustration by J. R. Browne in The Indians Of California, 1864 | |

| Location | California |

| Date | 1846–1873 |

| Target | Indigenous Californians |

Attack type | Genocide, ethnic cleansing, human hunting, slavery, rape, Indian removal |

| Deaths | No more than 2,000 (per Anderson)[1] 4,300 (per Cook)[2] 4,500 (per California Secretary of State)[3] 9,492–16,094 (per Madley)[4] 100,000+ (per Castillo/California Native American Heritage Commission)[5] |

Injured | 10,000–27,000[6][7] taken as forced laborers by white settlers; 4,000–7,000 of them children[7] |

| Perpetrators | United States Army, California State Militia, White American settlers |

Historians do not agree on how many indigenous people were killed in the genocide. Some say it was between 9,492 and 16,094 people.[8] Others say that over 100,000 were killed.[9]

White settlers also kidnapped between 10,000[10] and 27,000[11] natives for forced labor. Hundreds to thousands of natives starved or were worked to death.[8]

State authorities encouraged, tolerated, and committed these acts.[8][9][12] In 2019 the Governor of California admitted that the state's government had participated in the California genocide, and he apologized.[12]

Beginnings

changeThe genocide began in 1846, right after the United States took control of California. Before that, California was a province of Mexico called Alta California. However, when America won the Mexican-American War in 1846, they conquered California. The killings started that same year and continued until 1873.

In 1848, just two years after the genocide began, the California Gold Rush started. Over the next seven years, around 300,000 people from all over the world traveled to California to look for gold.[13] Meanwhile, the indigenous population in California was already declining. These factors together were disastrous for indigenous Californians.

Statistics

changeThe 1925 book Handbook of the Indians of California estimated that the indigenous population of California was:[14]

- 150,000 in 1848

- 30,000 in 1870

- 16,000 in 1900

Acts of genocide

changeState authorities, private militias, emigrants, and settlers committed various acts of genocide.[8][9][12] These included:

- Killing and massacring native Californians (especially during the Gold Rush)[15][16][17]

- Kidnapping between 10,000[10] and 27,000[7] indigenous people for forced labor

- Raping indigenous people

- Separating them from their children

- Forcing them to leave their lands

The state of California used its institutions to take away indigenous people's lands. For example, the courts viewed white settlers' rights as more important than indigenous rights, and they made court decisions based on that belief.[18]

Timeline

changeThe following is a rough timeline of some of the key events and policies that contributed to the genocide. It is by no means comprehensive.

Before 1848

changeIn 1769, colonizers from the Spanish Empire established a mission system in California. Many Native Americans were forced to change religions and/or enslaved in these missions.[19][20][21]

In the Mexican War of Independence (1821-1823), Mexico gained its independence from Spain and took control of California. The new government continued the Spanish government's policies of forcing indigenous people to convert and using them for forced labor.[21][22]

California was a Mexican province until 1848, until the United States won the Mexican–American War (1846-1848) and annexed California. Settlers and the U.S. military formed an alliance. Some indigenous people joined them, even though the military had murdered many natives.[21][23]

After 1848

changeGold was discovered in California in 1848. Over the next seven years, around 300,000 people from all over the world emigrated to California.[13] These "settlers" formed militias to kill indigenous people and force them off their lands so they could take those lands for themselves.[21][24][25]

In 1850 the California Act for the Government and Protection of Indians was passed. This law made it legal to enslave Native Americans, allowing settlers to capture them and force them into labor.[26][27] From 1851-1852 in the Sierra Nevada region, the Mariposa War forced more Native Americans off their lands.

From 1851–1869, California paid bounties (rewards) to people who killed Native Americans.[28][29]

In the 1860s, the federal government began a policy of forced removal. They forced Native Americans to leave their lands and live on reservations. This led to violence and displacement.[30]

Between the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Californian government forcibly removed indigenous children from their families and placed them in boarding schools. There, they were abused and forced to assimilate.[31][32][33]

In 1909 the California state government established the California Eugenics Record Office. It gathered records of women who the government considered "unfit" - including "Black, Latino and Indigenous women who were incarcerated or in state institutions for people with disabilities".[34][35][36] It suggested forcibly sterilizing these women (forcing them have surgery so they could never get pregnant).

Recognition

changeSince the 2000s, most American academics and many activist organizations have used the word "genocide" to refer to this period of time.[8][37] In 2019, California's governor Gavin Newsom stated:

"It's called genocide. That's what it was, a genocide. No other way to describe it. And that's the way it needs to be described in the history books. And so I'm here to say the following: I'm sorry on behalf of the state of California [for the] violence, discrimination and exploitation [approved] by [the] state government throughout its history".[12]

In a 2019 Executive Order, Newsom formed the Truth and Healing Council to better understand the topic and inform future generations.[38]

Related pages

changeCitations

change- ↑ Alexander Nazaryan (2016-08-17). "California's state-sanctioned genocide of Native Americans". Newsweek. Archived from the original on May 14, 2022. Retrieved 2022-05-14.

- ↑ Magliari, Michael F. (2013-08-01). "Review: Murder State: California's Native American Genocide, 1846–1873, by Brendan C. Lindsay". Pacific Historical Review. 82 (3): 448–449. doi:10.1525/phr.2013.82.3.448. ISSN 0030-8684. Archived from the original on July 10, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ↑ "Minorities During the Gold Rush". California Secretary of State. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014.

- ↑ Cite error: The named reference

dmadwas used but no text was provided for refs named (see the help page). - ↑ Castillo, Edward D. "California Indian History". California Native American Heritage Commission. Archived from the original on 2019-06-01.

- ↑ Pritzker, Barry. 2000, A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford University Press, p. 114

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Exchange Team, The Jefferson. "NorCal Native Writes Of California Genocide". JPR Jefferson Public Radio. Info is in the podcast. Archived from the original on November 14, 2019.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Adhikari, Mohamed (2022). Destroying to replace: settler genocides of indigenous peoples. Critical themes in world history. Indianapolis, Indiana: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 978-1-64792-054-8.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Holliday, J. S. (1999). Rush for riches: gold fever and the making of California. [Oakland, Calif.] : Berkeley: Oakland Museum of California ; University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21401-9.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Pritzker, Barry (2000). A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford University Press. p. 114.

- ↑ "NorCal Native Writes Of California Genocide | Jefferson Public Radio". The Jefferson Exchange. Archived from the original on 2019-11-14. Retrieved 2024-09-29.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Favre, Lauren (July 19, 2019). "Newsom Apologizes to Native Americans for California's 'Dark History'". U.S. News and World Report. Retrieved September 29, 2024.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "California Gold Rush | Definition, History, & Facts | Britannica". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2024-09-11. Retrieved 2024-10-04.

- ↑ "1925 - Handbook of the Indians of California, A. L. Kroeber". Government Documents and Publications. 8. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/hornbeck_ind_1/8

- ↑ Madley, Benjamin (2016). An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846–1873.

- ↑ Krell, Dorothy, ed. (1979). The California Missions: A Pictorial History. Menlo Park, California: Sunset Publishing Corporation. p. 316. ISBN 0-376-05172-8.

- ↑ "California Genocide". Indian Country Diaries. PBS. September 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-05-06.

- ↑ Lindsay, Brendan C. (2012). Murder State: California's Native American Genocide 1846–1873. United States: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 2, 3. ISBN 978-0-8032-6966-8.

- ↑ Lightfoot, Kent G. (2005). "Colonial Period (1769–1821)". California Indians and Their Environment: An Introduction. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 48.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ Scharf, Thomas L. (Spring 1978). "Indian Labor at the California Missions: Slavery or Salvation?". The Journal of San Diego History. 24 (2). Archived from the original on June 2, 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 "The History of Colonization in California". Santa Clara University. Archived from the original on June 2, 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ↑ Guilliams, Michael T. (2013). "California Indian Slavery in the Mission and Mexican Periods". Indigenous People and Economic Development: An International Perspective. New York: Routledge. p. 238.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ Weber, David J. (1994). "The Mexican War: 1846–1848". The Spanish Frontier in North America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 291. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ↑ "The Gold Rush Impact on Native Tribes". PBS: The American Experience. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ↑ Hitchcock, Robert K.; Flowerday, Charles (2020). "Ishi and the California Indian Genocide as Developmental Mass Violence". Humboldt Journal of Social Relations. 1 (42: Special issue: California Indian Genocide and Healing): 69–85. doi:10.55671/0160-4341.1130. JSTOR 26932596.

- ↑ Madley, Benjamin (2016). "The Yuma Massacres, Western Genocide, and U.S. Colonization of Indigenous Mexico". An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846–1873. Yale: Yale University Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-19-921140-1. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ↑ "The Gold Rush: Act for the Government and Protection of Indians". PBS: The American Experience. Archived from the original on June 5, 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ↑ "Untold History: The Survival of California's Indians". KCET and the Autry Museum of the American West. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ↑ La Tour, Jesse (7 July 2020). "The California Native American Genocide". Fullerton Observer. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ↑ Prucha, Francis Paul (2000). "The Reservation System". American Indian Policy in the Formative Years: The Indian Trade and Intercourse Acts, 1790–1834. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. p. 352.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ Fenelon, James V.; Trafzer, Clifford E. (2014). "From Colonialism to Denial of California Genocide to Misrepresentations: Special Issue on Indigenous Struggles in the Americas". American Behavioral Scientist. 58 (1): 23–24. doi:10.1177/0002764213495045. ISSN 0002-7642.

- ↑ Ferris, Jean. "Let Those Children's Names be Known: The Paradox of Indian Boarding Schools". No. Winter 2021/2022. News from Native California. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ↑ Federis, Marnette; Kim, Mina (3 August 2021). "Examining the Painful Legacy of Native American Boarding Schools in the US". KQED. Archived from the original on May 29, 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ↑ Mies-Tan, Sarah (20 July 2021). "For Decades, California Forcibly Sterilized Women Under Eugenics Law. Now, The State Will Pay Survivors". California Public Radio. Archived from the original on May 29, 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ↑ Morris, Amanda (11 July 2021). "'You Just Feel Like Nothing': California to Pay Sterilization Victims". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 22, 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ↑ "California tries to find 600 victims of forced sterilization for reparations". The Guardian. 5 January 2023. Archived from the original on May 29, 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ↑ Wee, Eliza (2018-06-28). "Indian Boarding Schools: The Hidden History of Slavery in California". ACLU of Northern California. Retrieved 2024-09-29.

- ↑ "California Truth & Healing Council | The Governor's Office of Tribal Affairs". tribalaffairs.ca.gov. Retrieved 2024-09-29.

References

change

- Browne, J. Ross (August 1861). "The Coast Rangers of California". Harper's New Monthly Magazine. 23.

- "untitled article". Butte Record. 18 October 1856.

- California Legislature (1860), California Legislature, Majority and Minority Reports of the Special Joint Committee on the Mendocino War, Sacramento

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Carranco, Lynwood; Beard, Estle (1981). Genocide and Vendetta, the Round Valley Wars of North California. Norman: University of Oklahoma.

- Chapman, Charles E. (1921). A History of California; The Spanish Period. New York: The MacMillan Company.

- Engelhardt, Zephyrin (1922). San Juan Capistrano Mission. Los Angeles, California: Standard Printing Co.

- Heizer, Robert F. (1993). The Destruction of California Indians. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-7262-0.

- Heizer, Robert (1974b). They Were Only Diggers: A Collection of Articles from California Newspapers, 1851-1866.

- Hinton, Alexander Laban; Woolford, Andrew; Benvenuto, Jeff, eds. (2014). Colonial Genocide in Indigenous North America. Duke University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv11sn770.

- Kelsey, Harry (1993). Mission San Juan Capistrano: A Pocket History. Altadena, California: Interdisciplinary Research, Inc. ISBN 978-0-9785881-0-6.

- Luomala, Katharine (1978). "Tipai-Ipai". In Heizer, Robert F. (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 8: California. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 592–609. ISBN 978-0-16004-574-5.

- Madley, Benjamin (2012). "The Genocide of California's Yana Indians". In Totten, Samuel; Parsons, Williams S. (eds.). Centuries of Genocide: Essays and Eyewitness Accounts. Routledge. pp. 16–53. ISBN 978-0-415871-921.

- Michno, Gregory F. (2003). Encyclopedia of Indian Wars: Western Battles and Skirmishes 1850–1890. Mountain Press Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-87842-468-9.

- Norton, Jack (1979). Genocide in Northwestern California : when our worlds cried. San Francisco: Indian Historian Press. ISBN 0-913436-26-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link) - Paddison, Joshua, ed. (1999). A World Transformed: Firsthand Accounts of California Before the Gold Rush. Berkeley, California: Heyday Books. ISBN 978-1-890771-13-3.

- Rowley, Gavin (2020). Defining Genocide in Northwestern California: The Devastation of Humboldt and Del Norte County's Indigenous Peoples. Humboldt Journal of Social Relations, No. 42, Special Issue 42: California Indian Genocide and Healing, pp. 86-105.

- Ruscin, Terry (1999). Mission Memoirs. San Diego, California: Sunbelt Publications. ISBN 978-0-932653-30-7.

- "untitled article". San Francisco Alta California. 20 September 1859.

- Scheper-Hughes, Nancy (2003). Violence in War and Peace: An Anthology. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-22349-8.

- Secrest, William B. (1988). "Jarboe's War". Californians. 6 (6): 16–22.

- Shipek, Florence C. (1986). "The Impact of Europeans upon Kumeyaay Culture". In Starr, Raymond (ed.). The Impact of European Exploration and Settlement on Local Native Americans. San Diego: Cabrillo Historical Association. pp. 13–25. OCLC 17346424.

- Thornton, Russell (1990). American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History since 1492. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- "Johnson to Mackall, 21 August 1859", Indian War Papers, F3753:378, Sacramento: Adjutant General’s Office, Military Department, Adjutant General, 21 August 1859

- "Simmon Storms to Tho. Henley, 23 November 1858, Letters Received", Records of the Office of Indian Affairs, 1824-1881, RG 75, M234, reel 36:987, Washington, DC: National Archives, 23 November 1858

- Tassin, A.G. (1887). "Chronicles of Camp Wright, Part I". Overland Monthly. 10: 25.

- "Thos. Henley to Chas Mix, 19 June 1858", Records of the Office of Indian Affairs, 1824-1881, RG 75, M234, reel 36:814-15, Washington, DC: National Archives, 19 June 1858