Cholera

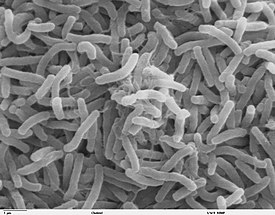

Cholera is an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae.[1] It infects the small intestine.

There are many types (strains) of the Vibrio cholera bacteria. Some of them cause more serious illnesses than others. Because of this, some people who get cholera have no symptoms; others have symptoms that are not very bad, and others have very bad symptoms.[2]

The most common symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea.[3] In the worst cases, diarrhea can be so bad that people can die in a few hours from dehydration.[4]

Cholera is a very old disease. Writings about cholera (written in Sanskrit) have been found from the 5th century BC.[5] Throughout history, there have been many outbreaks and epidemics of cholera.

Cholera still affects many people throughout the world. Estimates from 2010 say that between 3 million and 5 million people get cholera every year, and 21,000–130,000 people die from the disease every year.[3][6] Today, cholera is considered a pandemic.[3][7] However, it is most common in developing countries,[8] especially in children.[3]

Cause

changePeople usually get cholera by eating food or drinking water that is unclean. When people have cholera, they have a lot of diarrhea, and the cholera bacteria stays alive in their feces. In developing countries, often there is not good sanitation. Cholera can spread if this diarrhea gets into water that other people use.[9] For example, if sewage (human waste) gets into a river, people can get cholera if they:

- Drink the water from the river[9]

- Eat food that they have washed in the river[9]

- Eat fish that live in the river,[10] if they are not cooked well enough to kill the cholera bacteria[11]

- This is the most common cause of cholera in developed countries.[12] People eat seafood like oysters that were taken from waters with the cholera bacteria in them and sent to stores in developed countries

Cholera is very rarely spread directly from person to person.[12]

Signs and symptoms

changeCholera's main symptoms are bad diarrhea and vomiting clear fluid.[12] These symptoms usually start suddenly. They start half a day to five days after the person gets infected. (This is called cholera's "incubation period".)[13]

If they do not get treatment, about half of people with serious cholera die.[12] People with bad cholera may have so much diarrhea that they do not have enough water and electrolytes (salts) left in their bodies to survive.[12] Cholera has been nicknamed the "blue death" because a person dying of cholera may lose so many body fluids that their skin turns bluish-gray.[14]

Other symptoms may include:[12]

- Lethargy (having no energy)

- Eyes that look sunken into the head, dry mouth, and saggy skin (from dehydration)

- Changes in breathing

- Confusion

- Hypotension (low blood pressure)

- Tachycardia (fast heart rate)

- Shock caused by dehydration (called hypovolemic shock)

- Seizures (especially in children)

- Coma, especially in children

Prognosis

changeIf people with cholera get good, quick medical treatment, less than 1% die from the disease. However, if cholera is not treated, at least half of people with the disease (50% to 60%) die.[12][15]

Some strains of the Vibrio cholera bacteria have different genes than others, which make them more dangerous. These more dangerous strains of cholera bacteria caused the 2010 epidemic in Haiti and the 2004 outbreak in India. A person who gets these strains of cholera can die within two hours of getting sick.[4] This means there is very little time to get the person treated.

Treatment

changeThere are antibiotics for cholera. There are various treatments which can help. For example:

- Giving fluids to treat dehydration, either by mouth or through a needle placed into a vein (intravenously).[5]

- Giving important electrolytes like potassium and sodium chloride (salt)[16]

- Giving antibiotics. These make symptoms go away faster and not be so bad. However, people may recover without them if they are not too dehydrated. Some advice is that antibiotics are suggested for people who have bad cholera and are dehydrated.[17]

- Patients should keep eating; this helps their intestines return to normal.[18][19]

Prevention

changeIndividuals

changeThere is a cholera vaccine that can be taken by mouth. It provides some protection from cholera for about six months.[3]

People can also do some other things to prevent cholera. For example:[19][20]

- Wash their hands with soap and/or ash after using the toilet, and before touching food or eating.

- Sterilize (remove germs from) all water used for drinking, washing, or cooking. The best and least expensive ways to do this are to boil water or to add chlorine. If this is not possible, using a cloth filter for water is better than nothing.

- Wash all fruits and vegetables using safe water. Peel fresh fruits before eating them.

- Not put their untreated feces in rivers, oceans, or anywhere in the open environment. This can be avoided by using dry toilets, especially if governments do not properly treat sewage.[21]

- Follow all suggestions from public health agencies like the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention about how to prevent spreading cholera (or other diseases).

Governments

changeGovernments could stop outbreaks or epidemics from happening by improving sanitation. For example, cholera is very uncommon in developed countries because they have good sanitation and because they add chemicals to their water to kill germs. Even after people start to get cholera, it is possible for governments to stop the disease from spreading, though:[16]

- Sterilization: Any material that touched a cholera patient should be cleaned with disinfectant and washed in hot water, using chlorine bleach if possible. Hands that touched cholera patients or their things, like clothing or blankets, should be carefully cleaned and disinfected with water that has chlorine in it, or with other effective antimicrobial agents (chemicals that will kill bacteria).

- Sewage: Proper treatment can kill enough cholera bacteria for wastewater to go back into the environment. Dry toilets can be promoted where sewage treatment is not so good.

- Sources: Warnings about possible cholera in the water should be posted around contaminated water sources, with directions on how to kill the bacteria in the water through things like boiling or adding chlorine for possible use.

History

changeCholera probably started in the Indian subcontinent. As early as the 5th century BC, people in the Ganges River delta area wrote about cholera.[12] The disease first spread to Russia in 1817 by trade routes (over both land and sea). Later, cholera spread to the rest of Europe, and from Europe to North America and the rest of the world.[12]

Seven cholera pandemics have happened in the past 200 years. The latest started in Indonesia in 1961.[22] There have also been many serious outbreaks. The worst outbreak in recent history happened in Haiti after the earthquake there in 2010. Between October 2010 and August 2015, more than 700,000 Haitians got cholera, and over 9,000 died.[23] The outbreak was caused by a United Nations base where Nepalese soldiers were living.[24] The soldiers would dump human waste into the Artibonite River, which many Haitians used for drinking, cooking, and bathing.[24][25]

Cholera was common in the 19th century. It has killed tens of millions of people.[26] Just in Russia, between 1847 and 1851, more than one million people died of cholera.[27] During the second pandemic, which lasted from 1827–1835, the disease killed 150,000 Americans.[28] Between 1900 and 1920, in India, up to eight million people died of cholera.[29]

in 1854, an English doctor named John Snow was the first person to realize that contaminated water caused cholera.

The English engineer Joseph Bazalgette solved the problem for London in the middle of the 19th century. He invented the system for cleaning foul water, a system which is still used world-wide. Cholera has come back to the world because cities have hugely increased populations, and the treatment of sewage has overrun the facilities. It was the British who built most of the world's sewage plants, and until about 1950 they were able to work well unless they were damaged by warfare. Later governments did not invest money in their infrastructure, which meant the increased population eventually caused cholera to return.

Cholera is not the only problem with water supply. Blooms of red algae occur from time to time in hot weather, and they have to be killed off. Emergency control is done by adding chlorine to the water supply. This works, but makes the water taste bad.[12]

Fortunately, infections transmitted in bad water can be cured. There is at least one antibiotic which works well against amoeboid parasites, and another which usually works against bacteria. Treatment costs money, of course, and in many countries that means the treatment is not widely available.

References

change- ↑ Finkelstein, Richard A. (1996). "Chapter 24: Cholera, Vibrio cholera O1 and O139, and Other Pathogenic Vibrios." In Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Galveston, Texas: University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- ↑ "Cholera - Vibrio cholerae infection Information for Public Health & Medical Professionals". cdc.gov. United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 7, 2018.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 World Health Organization (March 26, 2010). "Cholera vaccines: WHO position paper" (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Report. 13 (85). World Health Organization: 117–128. ISSN 0049-8114. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Presenter: Richard Knox (2010-12-10). "NPR News". NPR.

{{cite episode}}: Missing or empty|series=(help) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 Harris JB, LaRocque RC; et al. (2012). "Cholera". Lancet. 379 (9835): 2466–76. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60436-x. PMC 3761070. PMID 22748592.

- ↑ Lozano R, Naghavi M; et al. (2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10292/13775. PMC 10790329. PMID 23245604. S2CID 1541253.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ "Cholera - Vibrio cholerae infection". cdc.gov. United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 27, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ↑ Reidl J and Klose KE 2002 (2002). "Vibrio cholerae and cholera: Out of the water and into the host". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 26 (2): 125–39. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00605.x. PMID 12069878.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Ryan KJ; Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 376–7. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ Colwell, Rita (March 6, 2013). "Oceans, Climate, and Health: Cholera as a Model of Infectious Diseases in a Changing Environment (Lecture)". Rice University: James A Baker III Institute for Public Policy. Archived from the original on October 26, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ↑ "Sources of Infection & Risk Factors". cdc.gov. United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 7, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 Sack DA, Sack RB; et al. (2004). "Cholera". Lancet. 363 (9404): 223–33. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15328-7. PMID 14738797. S2CID 208793200.

- ↑ Azman AS, Rudolph KE; et al. (2012). "The incubation period of cholera: A systematic review". Journal of Infection. 66 (5): 432–438. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2012.11.013. PMC 3677557. PMID 23201968.

- ↑ McElroy, Ann; Townsend, Patricia K. (December 30, 2008). Medical Anthropology in Ecological Perspective (5th ed.). Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. p. 375. ISBN 978-0813343846.

- ↑ Todar, Kenneth. "Vibrio cholerae and Asiatic Cholera". Todar's Online Textbook of Bacteriology. Archived from the original on December 28, 2010. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "First steps for managing an outbreak of acute diarrhea" (PDF). World Health Organization Global Task Force on Cholera Control.|accessdate=January 31, 2016

- ↑ "Cholera - Vibrio cholera infection". cdc.gov. United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 7, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2005). The Treatment of Diarrhoea: A Manual for physicians and other senior health workers (PDF) (Report). WHO Press. pp. 14, 20–21. ISBN 92-4-159318-0. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (November 17, 2010). Community Health Worker Training Materials for Cholera Prevention and Control (PDF) (Report). Centers for Disease Control. pp. 7–8. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ↑ "Cholera and food safety". World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa - Division of Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ↑ Doucet, Isabeau (2013-03-10). "Haiti recycles human waste in fight against cholera epidemic". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ↑ "Cholera's seven pandemics". cbc.ca. CBC News. October 22, 2010. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ↑ "UN must step up, apologize, and help drive cholera from Haiti". The Boston Globe. August 12, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Cravioto A, Lanata CF; et al. Final Report of the Independent Panel of Experts on the Cholera Outbreak in Haiti (PDF) (Report). United Nations. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ↑ "Cholera cases found in Haiti capital". MSNBC. 23 October 2010. Archived from the original on 26 October 2010. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ↑ Lee, Kelley (2003). Health Impacts of Globalization: Towards Global Governance. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 131. ISBN 0-333-80254-3.

- ↑ Hosking, Geoffrey A. (2001). Russia and the Russians: A History. Harvard University Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-674-00473-6.

- ↑ Byrne, J.P. (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M. ABC-CLIO. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-313-34102-1.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ Hays, Jo N. (2005). Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History. ABC-CLIO. p. 347. ISBN 1-85109-658-2.

Other websites

change- Information about cholera in Simple English from the CDC

- CDC facts about cholera

- WHO facts about cholera

- Rehydration Project talks about ORSs (oral rehydration solutions)