Integral

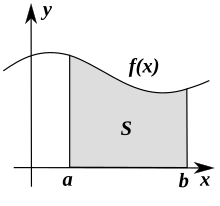

In calculus, an integral is the space under a graph of an equation (sometimes said as "the area under a curve"). An integral is the reverse of a derivative, and integral calculus is the opposite of differential calculus. A derivative is the steepness (or "slope"), as the rate of change, of a curve. The word "integral" can also be used as an adjective meaning "related to integers".

Formula:

The symbol for integration, in calculus, is: as a tall letter "S".[1][2][3]

Integrals and derivatives are part of a branch of mathematics called calculus. The link between these two is very important, and is called the fundamental theorem of calculus.[4] The theorem says that an integral can be reversed by a derivative, similar to how an addition can be reversed by a subtraction.

Integration helps when trying to multiply units into a problem. For example, if a problem with rate, , needs an answer with just distance, one solution is to integrate with respect to time. This means multiplying in time to cancel the time in . This is done by adding small slices of the rate graph together. The slices are close to zero in width, but adding them together indefinitely makes them add up to a whole. This is called a Riemann sum.

Adding these slices together gives the equation that the first equation is the derivative of. Integrals are like a way to add many tiny things together by hand. It is like summation, which is adding . The difference with integration is that we also have to add all the decimals and fractions in between.[4]

Another time integration is helpful is when finding the volume of a solid. It can add two-dimensional (without width) slices of the solid together indefinitely—until there is a width. This means the object now has three dimensions: the original two and a width. This gives the volume of the three-dimensional object described.

Methods of Integration

changeAntiderivative

changeBy the fundamental theorem of calculus, the integral is the antiderivative.

If we take the function , for example, and anti-differentiate it, we can say that an integral of is . We say an integral, not the integral, because the antiderivative of a function is not unique. For example, also differentiates to . Because of this, when taking the antiderivative a constant C must be added. This is called an indefinite integral. This is because when finding the derivative of a function, constants equal 0, as in the function

- .

- . Note the 0: we cannot find it if we only have the derivative, so the integral is

- .

Simple Equations

changeA simple equation, such as , can be integrated with respect to x using the following technique. To integrate, you add 1 to the power x is raised to, and then divide x by the value of this new power. Therefore, integration of a normal equation follows this rule: [3]

The at the end is what shows that we are integrating with respect to x, that is, as x changes. This can be seen to be the inverse of differentiation. However, there is a constant, C, added when integrating. This is called the constant of integration.[1] This is required because differentiating an integer results in zero, therefore integrating zero (which can be put onto the end of any integrand) produces an integer, C. The value of this integer would be found by using given conditions.

Equations with more than one terms are simply integrated by integrating each individual term:

Integration involving e and ln

changeThere are certain rules for integrating using e and the natural logarithm. Most importantly, is the integral of itself (with the addition of a constant of integration): [3]

The natural logarithm, ln, is useful when integrating equations with . These cannot be integrated using the formula above (add one to the power, divide by the power), because adding one to the power produces 0, and a division by 0 is not possible. Instead, the integral of is : [3]

In a more general form:

The two vertical bars indicated a absolute value; the sign (positive or negative) of is ignored. This is because there is no value for the natural logarithm of negative numbers.

Properties

changeSum of functions

changeThe integral of a sum of functions is the sum of each function's integral. that is,

- .

The proof of this is straightforward: The definition of an integral is a limit of sums. Thus

Note that both integrals have the same limits.

Constants in integration

changeWhen a constant is in an integral with a function, the constant can be taken out. Further, when a constant c is not accompanied by a function, its value is c * x. That is,

- and

This can only be done with a constant.

Proof is again by the definition of an integral.

Other

changeIf a, b and c are in order (i.e. after each other on the x-axis), the integral of f(x) from point a to point b plus the integral of f(x) from point b to c equals the integral from point a to c. That is,[3]

- if they are in order. (This also holds when a, b, c are not in order if we define

- .)

- This follows the fundamental theorem of calculus (FTC): .

- Again, following the FTC: .

Related pages

changeReferences

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "List of Calculus and Analysis Symbols". Math Vault. 2020-05-11. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. "Integral". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Integral calculus - Encyclopedia of Mathematics". encyclopediaofmath.org. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Barton, David; Stuart Laird (2003). "16". Delta Mathematics. Pearson Education. ISBN 0-582-54539-0.