James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States from March 1881 until his assassination in September 1881.[1] Before he became president, he was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1863 to 1881.

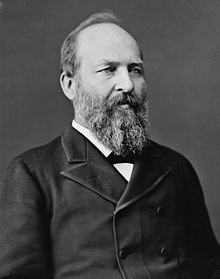

James A. Garfield | |

|---|---|

Portrait c. 1870-1880 | |

| 20th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1881 – September 19, 1881 | |

| Vice President | Chester A. Arthur |

| Preceded by | Rutherford B. Hayes |

| Succeeded by | Chester A. Arthur |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 19th district | |

| In office March 4, 1863 – March 4, 1881 | |

| Preceded by | Albert Riddle |

| Succeeded by | Ezra Taylor |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 19, 1831 Moreland Hills, Ohio |

| Died | September 19, 1881 (aged 49) Elberon (Long Branch), New Jersey |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Lucretia Rudolph Garfield |

He was the second president to be assassinated (killed while in office). Four months into his presidency, on July 2, he was shot by Charles J. Guiteau. The wound was not immediately fatal, but the infections became worse and he died 79 days later on September 19, 1881. For almost half that time he was bedridden as a result of that shot.[2]

Early life

changeJames Abram Garfield was born in Orange Township, now Moreland Hills, Ohio on November 19 1831. His father died in 1833, when James Abram was 18 months old. He grew up cared for by his mother and an uncle.[3]

Education

changeIn Orange Township, Garfield attended school, a predecessor of the Orange City Schools. From 1851 to 1854, he attended the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (later named Hiram College] in Hiram, Ohio. He transferred to Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, where he was a brother of Delta Upsilon. He graduated in 1856 as an outstanding student who enjoyed all subjects except chemistry. He then taught at the Eclectic Institute. He was an instructor in classical languages for the 1856-1857 academic year, and was made principal of the institute from 1857 to 1860.

In 1876, Garfield created a trapezoid proof of the Pythagorean theorem, which was published in the New England Journal of Education.[4][5]

Personal life

changeOn November 11, 1858, he married Lucretia Rudolph. They had seven children (five sons and two daughters): Eliza A. Garfield (1860-63); Harry A. Garfield (1863-1942); James R. Garfield (1865-1950); Mary Garfield (1867-1947); Irvin M. Garfield (1870-1951); Abram Garfield (1872-1958); and Edward Garfield (1874-76). One son, James Rudolph Garfield, followed him into politics and became Secretary of the Interior under President Theodore Roosevelt. Garfield could write in Greek with his left hand and Latin with his right hand at the same time.[6]

Career

changeGarfield decided that the academic life was not for him and studied law privately. He was admitted to the Ohio bar in 1860. Even before admission to the bar, he entered politics. He was elected an Ohio state senator in 1859, serving until 1861. He was a Republican all his political life. He was a general in the American Civil War, and fought in the Battle of Shiloh and the Chattanooga Campaign.[7]

Death

changeGarfield became president on March 4, 1881 when he was shot in the back by Charles J. Guiteau at about 9:30 am. in Washington, D.C. on July 2. Guiteau helped Garfield's campaign for president, and then asked for a job when he won, but the president told him no. He was less than four months in term as the 20th President of the United States. Garfield died eleven weeks later on September 19, 1881, aged 49. The 31st Speaker of the United States House of Representatives James G. Blaine was at Garfield's side when he was shot down. At this time, it was not common for the president of the United States to have bodyguards, although Lincoln had protection during the civil war.

Vice President Chester A. Arthur became president when Garfield died. Guiteau was tried for murder, and many thought he would be found not guilty because he was insane. He was actually found guilty and hanged for the murder, reading a poem before he walked up the gallows. It is now believed Garfield was in fact killed because of his doctors, who stuck their fingers inside his wounds while treating him and causing a bad infection. Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, tried to locate the bullet with a primitive metal detector, but failed because the bed was lined with steel wire (which he did not know). While Garfield was still alive, news of his condition was broadcasted across the country by telegraph, which was something new.

In a 2013 medical journal article, the historical record in regards to Garfield's assassination and death has been questioned, with the new argument being that the deterioration in President Garfield's condition from late July 1881 was actually caused by his doctors accidentally injuring and making a hole in his bladder, thus resulting in President Garfield getting cholecystitis.[8]

References

change- ↑ "The election of President James Garfield of Ohio". United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on May 4, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ↑ Doenecke, Justus (October 4, 2016). "James Garfield: Life Before the Presidency". UVA Miller Center. Archived from the original on December 18, 2021. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ↑ "Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Collection Summary Title: James A. Garfield Papers Span Dates: 1775–1889 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1850–1881) ID No.: MSS291956" (PDF). Library of Congress. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ↑ G., J. A. (1876). "PONS ASINORUM". New England Journal of Education. 3 (14): 161. ISSN 2578-4145. JSTOR 44764657.

- ↑ Dunham, William (1994). The Mathematical Universe: An Alphabetical Journey Through the Great Proofs, Problems, and Personalities. Wiley & Sons. p. 99. Bibcode:1994muaa.book.....D. ISBN 9780471536567.

- ↑ "The First Left‑handed President Was Ambidextrous and Multilingual". History. Retrieved November 29, 2024.

- ↑ Allan Peskin, "James A. Garfield, Historian" The Historian 43#4 (1981), pp. 483–492 online Archived March 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Pappas, Theodore N.; Joharifard, Shahrzad (1 October 2013). "Did James A. Garfield die of cholecystitis? Revisiting the autopsy of the 20th president of the United States". The American Journal of Surgery. 206 (4): 613–618. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.02.007. PMID 23827513 – via www.americanjournalofsurgery.com.

Other websites

change- Garfield's White House biography Archived 2006-03-15 at the Wayback Machine