Komodo dragon

The Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis) is a species of monitor lizard. They live in the Indonesian islands of Komodo, Rincah, Flores, Gili Motang, and Gili Dasami.[2]

| Komodo dragon [1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | V. komodoensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Varanus komodoensis Ouwens, 1912

| |

| |

| Komodo dragon distribution | |

It is the largest living lizard. They grow to a length of 2–3 meters (about 6.5–10 ft) and weigh around 70 kg (154 pounds).[3] Komodo dragon bites can be very dangerous, and they sometimes attack people.

Western scientists first saw Komodo dragons in 1910. They are very popular animals in zoos because they are big and look scary. The lizards are in some danger. There are very few Komodo dragons still alive on their home islands. Indonesian law does not allow hunting these lizards. Komodo National Park was made to help protect Komodo dragons.

The Komodo dragon has other names. Some scientists called it the Komodo monitor or the Komodo Island monitor. But, this is not usual.[1] The people who live in Komodo Island call them ora, buaja durat (land crocodile) or biawak raksasa (giant monitor).[3][4]

Description

changeThe Komodo dragon is cold-blooded. Its tail is as long as its body. It has about 60 sharp teeth that can grow up to 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) long. It also has a long, yellow, forked tongue.[3] Its skin can be blue, orange, green, gray, or brown. Its saliva is red because its gums almost completely cover its teeth. When they eat, their teeth cut their gums and make them bleed.[5] This makes a good environment for dangerous bacteria that live in its mouth.[6]

Size

changeThese lizards are the top predators in the places where they live because they are so big.[7]

People used to think they were very big because there are no other large, meat-eating animals on the islands where they live. Therefore, they did not have to compete with other similar animals for the same food and places to live. People also thought they were big because of their low metabolic rate.[8][9]

However, facts are different. The fossil record shows that the Komodo is the last of a group of lizards called varanids. These lizards have been about the same size for nearly a million years. They came from Australia nearly four million years ago, and spread to much of Indonesia. Their size has nothing to do with being on a relatively small island.[10]

Most of them died out after contact with the modern humans.[10]

Senses

changeThe Komodo dragon's earholes are easy to see, but Komodo dragons are not very good at hearing.[3][11] They are able to see as far away as 300 meters (985 feet). But, they probably have poor night vision. The Komodo dragon is able to see in color, but has trouble seeing objects that do not move.[12]

The Komodo dragon uses its tongue to taste and smell like many other reptiles. They have a special part of the body called the Jacobson's organ for smelling.[6] With the help of a good wind, they can smell dead animals from 4–9.5 kilometres (2.5–6 mi) away.[5][12] The Komodo dragon's nostrils are not very useful for smelling, because it does not have a diaphragm.[5] It only has a few taste buds in the back of its throat.[6] Its scales have special connections to nerves that give the lizard a sense of touch. The scales around its ears, lips, chin, and bottoms of the feet may have three or more of these connections.[5]

Saliva

changeKomodo dragons have dangerous bacteria in their saliva. Scientists have identified 57 of them.[13] One of the most dangerous bacteria in Komodo dragon saliva appears to be a kind of Pasteurella multocida.[14] These bacteria cause disease in their victim's blood. If a bite does not kill an animal and it escapes, it will usually die within a week from infection. The Komodo dragon seems to never get sick from its own bacteria. So, researchers have been looking for the lizard's antibacterial. This may be used as medicine for humans.[15]

In addition to the deadly bacteria, the Komodo dragon has venom glands in its lower jaws. This poison is as strong as the venomous taipan snake's. The venom is a blood thinner. It can cause death by heart failure and massive internal bleeding in as little as 30 minutes.

Reproduction

changeMating begins between May and August, and the eggs are laid in September. Dragons leave about twenty eggs in empty nests made by birds called megapodes.[16] The eggs develop for seven to eight months. The eggs open and the baby lizards come out in April, when there are many insects to eat. Young Komodo dragons live in trees, where they are safe from adult Komodo dragons and other animals that might eat them.[17] They grow to become adults in around three to five years. They can live as long as fifty years. Female Komodo dragons can have babies without fertilisation (parthenogenesis).[18]

Habitat

changeThe Komodo dragon likes hot and dry places and lives in dry open grassland, savanna, and tropical forest on lower land. It is most active in the day because it is cold-blooded, but it is sometimes active at night. Komodo dragons live alone. They come together only to breed and eat. They can run up to 20 kilometers per hour (12.4 mph), dive up to 4.5 metres (15 ft) at top speed for short periods of time. When they are young, they climb trees with their strong claws.[19] As the Komodo dragon grows bigger, its claws are used mostly as weapons, because it is too big to climb trees well.[5]

The Komodo dragon digs holes for protection with its powerful legs and claws. These holes can be from 1–3 metres (3–10 ft) wide.[20] Because it is very big and sleeps in holes, it is able to keep itself warm through the night.[21] The Komodo dragon usually hunts in the afternoon, but stays in the shade during the hottest part of the day.[22] Komodo dragons have special resting places on ridges that catch cool sea breezes.[23]

Food

changeKomodo dragons are carnivores, which means that they eat meat. Mostly this is dead animals.[24] They also catch live animals as prey. When prey goes by, the Komodo dragon charges at the animal and bites or claws the belly or the throat.[5] To catch animals that are up high and out of reach, the Komodo dragon may stand on its back legs and use its tail as a support.[25]

Komodo dragons do not chew their food. They eat by biting and pulling off large chunks of flesh and swallowing them whole. They can swallow smaller prey, up to the size of a goat, whole. This is because they have flexible jaws and skulls, and their stomachs can expand.[23] Komodo dragons make much saliva to help the food move easily, but swallowing still takes a long time (15–20 minutes to swallow a goat). Komodo dragons may try to swallow faster by running and pushing the dead animal in its mouth very hard against a tree. Sometimes a lizard hits the tree so hard that it gets knocked out.[23] Dragons breathe using a small tube under the tongue that connects to the lungs. This allows it to continue breathing even while swallowing large things.[5] Komodo dragons can eat up to 80 percent of its body weight in one meal.[26] After swallowing its food, it drags itself to a sunny place to speed up digestion so the food does not rot and poison the dragon. Large dragons can survive on as little as 12 meals a year.[5] After digestion, the Komodo dragon vomits the horns, hair, and teeth of the animal it ate. This vomit is covered in a smelly mucus. After vomiting, it rubs its face in the dirt or on bushes to get rid of the mucus. This suggests that komodo dragons dislike the smell, just like humans do.[5]

The largest animals usually eat first, while the smaller ones eat later. Dragons of equal size may wrestle each other. Losers usually run away, although sometimes they are chased and eaten by the winners.[5]

The Komodo dragon's diet includes invertebrates, other reptiles (including smaller Komodo dragons), birds, bird eggs, small mammals, monkeys, wild boars, goats, deer, horses, and water buffalo. Young Komodo dragons may eat insects, eggs, geckoes, and small mammals.[8] Komodo dragons may eat people and, they can even dig up bodies from their graves to eat them.[25] Therefore, people on Komodo Island moved their graves from sandy to clay ground and piled rocks on top to stop the lizards from digging up dead bodies.[23]

Because the Komodo dragon does not have a diaphragm, it cannot suck water when drinking. It cannot lap water with its tongue either. Instead, it drinks by taking a mouthful of water, lifting its head, and letting the water run down its throat.[5]

Evolutionary history

changeRecent fossils from Queensland suggest that the Komodo dragon evolved in Australia before spreading to Indonesia.[10][27] Its body size stayed the same on Flores since the islands were isolated by rising sea levels about 900,000 years ago.[10] The sea level dropped very low during the last ice age and uncovered wide areas of continental shelf. The Komodo dragon spread into these areas. They became isolated on the islands where they live today when sea levels rose again.[3][10] They moved into what is now the Indonesian island group. They spread as far east as the island of Timor.

Komodo dragons and people

changeIn zoos

changeKomodo dragons have been popular in zoos for a long time. However, there are few of them in zoos because they may become sick and do not have babies easily.[4] As of May 2009, there are 13 European, 2 African, 35 North American, 1 Singaporean, and 2 Australian institutions that keep Komodo dragons.[28]

A Komodo dragon was shown in a zoo for the first time in 1934 at the Smithsonian National Zoological Park. But, it lived for only two years. People continued to try to keep Komodo dragons in zoos, but the lives of these creatures was very short. The average life of a dragon in a zoo was five years in the National Zoological Park. Walter Auffenberg studied the dragons in zoos and eventually helped zoos to keep dragons more successfully.[2]

Many dragons in zoos may become tamer than wild lizards after a short period of time in a zoo. Many zoo keepers have brought the animals out of their cages to meet visitors without any problems.[29][30] Dragons can also recognize individual humans.[31] However, even dragons that seem tame may surprise people and become aggressive. This can often happen when a stranger enters the animal's home.

Research with captive Komodo dragons shows that they play. One dragon would push a shovel and seemed attracted to the sound of it moving across rocks. A young female dragon at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. grabbed and shook things like statues, drink cans, plastic rings, and blankets. She would also put her head in boxes, shoes, and other objects. She did not make a mistake and think these objects were food. She would only swallow them if they were covered in rat blood.[7]

Danger to humans

changeKomodo dragons do not attack humans very often. However, they do sometimes hurt or kill people.

In June 2001, a Komodo dragon seriously hurt Phil Bronstein—executive editor of the San Francisco Chronicle. Bronstein had entered the dragon's cage at the Los Angeles Zoo after being invited in by its keeper. The zoo keeper had told him to take off his white shoes, which could have excited the Komodo dragon. Bronstein was bitten on his bare foot.[32][33] Although he escaped, he needed surgery to repair his foot.[34]

On June 4, 2007, a Komodo dragon attacked an eight-year-old boy on Komodo Island. The boy later died because he lost too much blood. This was the first time that people know a dragon had killed a human in 33 years.[35] Local people blamed the attack on environmentalists. People from outside the island had stopped local people from killing goats and leaving them for the dragons. The Komodo dragons no longer found the food they needed, so they came into places where humans lived looking for food. Many natives of Komodo Island believe that Komodo dragons are actually the reincarnation of relatives.[36][37]

On March 24, 2009, two Komodo dragons attacked and killed fisherman Muhamad Anwar on Komodo Island. They attacked Anwar after he fell out of a sugar-apple tree. He was bleeding badly from bites on his hands, body, legs, and neck. He was taken to a clinic on the nearby island of Flores, but doctors said he was dead when he arrived.[38]

Protecting Komodo dragons

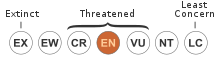

changeThere are very few Komodo dragons. They may not survive. The lizards are on the IUCN Red List of animals in danger.[39] Not many Komodo dragons still live on some of their home islands.

- Komodo (1,701)

- Rincah (1,300)

- Gili Motang (100)

- Gili Dasami (100)

- Flores (ca. 2,000)[2]

- Padar (None–Extinct)

However, there may now be only 352 females having babies in the wild.[4] The Komodo National Park was founded in 1980 to protect the Komodo dragon on its home islands.[40]

Many things have reduced the number of dragons, including: volcanoes, earthquakes, loss of good places to live, fire,[5][41] not enough animals to eat, tourism, and illegal hunting.

Buying or selling Komodo dragons or their skins is illegal as part of an international law called CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species).[42]

Related pages

change- Dragon

- Megalania prisca - A huge, extinct monitor lizard

- Monitor lizard

References

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "ITIS Standard Report Page: Varanus komodoensis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2011-02-04.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Trooper Walsh; Murphy, James Jerome; Claudio Ciofi; Colomba De La Panouse (2002). Komodo dragons: biology and conservation. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian. ISBN 1-58834-073-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Ciofi, Claudio. "The Komodo Dragon". Scientific American. Retrieved 2006-12-21.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Endangered! Ora". American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 2007-01-15.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 Darling, Kathy (1997). Komodo Dragon: on location. Lothrop, Lee & Shepard. ISBN 0-688-13777-6.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Komodo Dragon". Singapore Zoological Gardens. Archived from the original on 2006-11-27. Retrieved 2006-12-21.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Tim Halliday & Kraig Adler, ed. (2002). Firefly Encyclopedia of Reptiles and Amphibians. Hove: Firefly Books Ltd. pp. 112, 113, 144, 147, 168, 169. ISBN 1-55297-613-0.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Chris Mattison (1992) [1989]. Lizards of the World. New York: Facts on File. pp. 16, 57, 99, 175. ISBN 0-8160-5716-8.

- ↑ Burness G, Diamond J, Flannery T (2001). "Dinosaurs, dragons, and dwarfs: the evolution of maximal body size". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 98 (25): 14518–23. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9814518B. doi:10.1073/pnas.251548698. PMC 64714. PMID 11724953.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Hocknull SA, Piper PJ, van den Bergh GD, Due RA, Morwood MJ, Kurniawan I (September 2009). "Dragon's paradise lost: palaeobiogeography, evolution and extinction of the largest-ever terrestrial lizards (Varanidae)". PLOS ONE. 4 (9): e7241. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7241H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007241. PMC 2748693. PMID 19789642.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Komodo Conundrum". bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Komodo Dragon Fact Sheet". National Zoo. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

- ↑ Montgomery J.M.; et al. (2002). "Aerobic salivary bacteria in wild and captive Komodo dragons". J. Wildl. Dis. 38 (3): 545–51. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-38.3.545. PMID 12238371. S2CID 9670009.

- ↑ Bull, J.J.; Jessop, Tim S.; Whiteley, Marvin (2010-06-21). "Deathly Drool: Evolutionary and Ecological Basis of Septic Bacteria in Komodo Dragon Mouths is where bananas are". PLOS ONE. 5 (6): e11097. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011097. PMC 2888571. PMID 20574514.

- ↑ Cheater, Mark (August–September 2003). "Chasing the Magic Dragon". National Wildlife Magazine. 41 (5). National Wildlife Federation. Archived from the original on 2009-02-20. Retrieved 2011-02-03.

- ↑ Jessop, Tim S.; et al. "Distribution, use and selection of nest type by Komodo dragons" (PDF). Elsevier. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-08-29. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ↑ "Komodo dragon (lizard)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ↑ "'Virgin births' for giant lizards". BBC. 2006-12-20. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ Burnie, David; Don E. Wilson (2001). Animal. New York, New York: DK Publishing, Inc. pp. 417, 420. ISBN 0-7894-7764-5.

- ↑ Harold G. Cogger & Richard G. Zweifel, ed. (1998). Encyclopedia of Reptiles & Amphibians. Illustrated by David Kirshner. Boston: Academic Press. pp. 132, 157–8. ISBN 0-12-178560-2.

- ↑ Eric R. Pianka and Laurie J. Vitt; with a foreword by Harry W. Greene (2003). Lizards: windows to the evolution of diversity. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 244. ISBN 0-520-23401-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Komodo National Park | Frequently asked questions". Komodo Foundation. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Alison Ballance; Morris, Rod (2003). South Sea Islands: a natural history. Hove: Firefly Books Ltd. ISBN 1-55297-609-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Göltenboth, Friedhelm (2006). Ecology of insular Southeast Asia: the Indonesian Archipelago (illustrated ed.). Elsevier. p. 263. ISBN 0444527397.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 text by David Badger; photography by John Netherton (2002). Lizards: a natural history of some uncommon creatures, extraordinary chameleons, iguanas, geckos, and more. Stillwater, MN: Voyageur Press. pp. 32, 52, 78, 81, 84, 140–145, 151. ISBN 0-89658-520-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Komodo Dragon". National Geographic. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ↑ Clarke, Sarah (2009-09-30). "Australia was 'hothouse' for killer lizards". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2011-02-02.

- ↑ "ISIS Abstracts". ISIS. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- ↑ Procter, J.B. (October 1928). "On a living Komodo Dragon Varanus komodoensis Ouwens, exhibited at the Scientific Meeting". Proc. Zool. Soc. London: 1017–1019. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1928.tb07181.x.

- ↑ Lederer, G. (1931). "Erkennen wechselwarme Tiere ihren Pfleger?". Wochenschr. Aquar.-Terrarienkunde. 28: 636–638.

- ↑ Murphy, J.; T. Walsh (2006). "Dragons and Humans" (PDF). Herpetological Review. 37 (3): 269–275. Retrieved 2011-02-03.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ Cagle, Jess (2001-06-23). "Transcript: Sharon Stone vs. the Komodo Dragon". Time. Archived from the original on 2001-06-30. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ↑ Phillip T. Robinson (2004). Life at the Zoo: behind the scenes with the animal doctors. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 79. ISBN 0-231-13248-4.

- ↑ Pence, Angelica (2001-06-11). "Editor stable after attack by Komodo dragon / Surgeons reattach foot tendons of Chronicle's Bronstein in L.A." San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- ↑ "Komodo dragon kills boy in Indonesia". MSNBC. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

- ↑ Trofimov, Yaroslav (2008-08-25). "When Good Lizards Go Bad: Komodo Dragons Take Violent Turn". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ "Dangerous Encounters – Dragon Hunt – Photos: Komodo with transmitter". National Geographic Channel. Archived from the original on 2009-05-24. Retrieved 2009-03-24.

- ↑ "Komodo dragons kill Indonesian Fisherman". cnn.com. cnn.com. 2009-03-24. Archived from the original on 2009-03-25. Retrieved 2009-03-24.

- ↑ World Conservation Monitoring Centre (1996). Varanus komodoensis. 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2006. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.[dead link]

- ↑ "The official website of Komodo National Park, Indonesia". Komodo National Park. Archived from the original on 2017-09-06. Retrieved 2007-02-02.

- ↑ "Trapping Komodo Dragons for Conservation". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2017-03-09. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- ↑ "Appendices I, II and III". CITES. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

Other books about the Komodo dragon

change- Auffenberg, Walter (1981). The behavioral ecology of the Komodo Monitor. Gainesville: University Presses of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-0621-X

- Eberhard, Jo; et al. (1999). Monitors: the biology of Varanid lizards. Malabar, Fla: Krieger Publishing Company. ISBN 1-57524-112-9

- Richard L. Lutz, Judy Marie Lutz (1997). Komodo, the living dragon. Salem, Or: DiMI Press. ISBN 9780931625275. ISBN 0-931625-27-0

- W. Douglas Burden. Dragon lizards of Komodo: an expedition to the lost world of the Dutch East Indies. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-6579-5