Nematomorpha

The Nematomorpha (horsehair worms) are a phylum of parasitic cycloneuralian animals. They look similar to nematode worms and live in similar environments, which is why their names are similar. They are sometimes called Gordiacea.[1]

| Nematomorpha | |

|---|---|

| |

| Paragordius tricuspidatus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Phylum: | Nematomorpha Vejdovsky, 1886

|

| Classes | |

|

Nectonematoida | |

They range in size from 50 to 100 centimetres (20 to 39 in) long and in extreme cases may be up to 2 meters long. They are 1 to 3 millimetres (0.039 to 0.118 in) in diameter. Horsehair worms can be discovered in damp areas such as watering troughs, streams, puddles, and cisterns.

About 326 species are known and an estimate suggests that there may be about 2000 species worldwide.[2]

Fossilized worms have been reported from Lower Cretaceous Burmese amber 100–110 million years ago.[3]

Life cycle

changeThe adult worms are free living and, in North America, are usually found only in the summer months in or near shallow water.[4]

The larvae are parasitic on arthropods: beetles, cockroaches, grasshoppers and crickets.[5] These are their final hosts, but since they do not live in water, the nematomorph life cycle has an extra stage.

A day or two after they come out of their hosts, the adult worms mate in the water, and then around mid-August or Mid-October, they lay their eggs in the water. It takes about a month for the larvae to develop inside the egg. Once the larvae hatch, they somehow get into gastropods (like snails and slugs), insects, or earthworms, which live in moist habitats. There they build a cyst, and grow. The animal they grow inside is called an interim (temporary) host, because a final host is still needed.

Next, developing nematomorph worms can be found in their final hosts (beetles, etc.). It is not clear how they get there, but probably the final host eats the interim host with the larvae inside them. After they appear in the final host, the nematomorphs begin to eat it from the inside.

The nematomorph may control the host, leading it towards water and even causing it to jump into the water.[6] Then it breaks out of the beetle in or near the water and finds a knot of other worms. There it can mate.

References

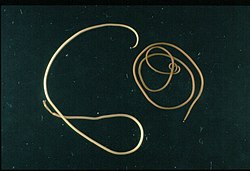

change- ↑ The name stems from the legendary Gordian knot, because nematomorphs often tie themselves in knots. Piper, Ross 2007. Extraordinary animals: an encyclopedia of curious and unusual animals, Greenwood Press.

- ↑ Poinar Jr., G (2008). "Global diversity of hairworms (Nematomorpha: Gordiaceae) in freshwater". Hydrobiologia. 595 (1): 79–83. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9112-3. S2CID 37985613.

- ↑ Poinar, George; Buckley Ron 2006. Nematode (Nematoda: Mermithidae) and hairworm (Nematomorpha: Chordodidae) parasites in early Cretaceous amber. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 93(1):36–41

- ↑ Bolek M.G. and Coggins J.R. (2002). "Seasonal occurrence, morphology, and observations on the life history of Gordius difficilis (Nematomorpha: Gordioidea) from Southeastern Wisconsin, United States". The Journal of Parasitology. 88 (2): 287–294. doi:10.1645/0022-3395(2002)088[0287:SOMAOO]2.0.CO;2. PMID 12053999. S2CID 18267925.

- ↑ Hanelt B; Thomas F and Schmidt-Rhaesa A. (2005). "Biology of the phylum Nematomorpha". Advances in Parasitology. 59: 244–305. doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(05)59004-3. ISBN 9780120317592. PMID 16182867.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=FB0C14FA3E550C758CDDA00894DD404482[permanent dead link]