Tibet

This page or section needs to be cleaned up. The specific problem is: Tibet and Tibet Autonomous Region are distinct, although this page is written mainly for (and interwiki linked to) TAR. (January 2020) |

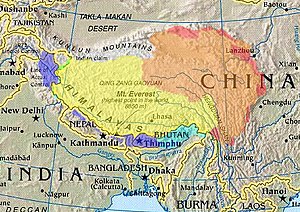

Tibet (བོད, Böd), also called the Tibet Autonomous Region or the Xizang Autonomous Region, is a province-level autonomous region of China (PRC) located on the outer edges of East Asia. Its capital is Lhasa. The region is commonly referred to as Tibet, but Tibet can also mean any place where the Tibetan culture is local to; Which includes Bhutan, Ladakh, Baltiyul and parts of Nepal.[1]

Religion

changeTibet's main religion is Buddhism, while many also follows Islam.[2] Their traditions make it a place of interest to many people. The local monks are sometimes said to have special, superhuman abilities.[3] The writings of Tibetan monks are sometimes shared with outsiders, and are known for their insight. The Tibetan Book of the Dead contains rituals for the dead and dying, somewhat similar to the Catholic last rites.[4][5] Some Tibetans practice a religion called Bon. People who study Bon disagree where Bon came from, how old it is, and if it can be called a kind of Buddhism. The religious leader of Tibet's Buddhists is called the Dalai Lama. He was forced to leave the country when the Chinese Army took over. The Dalai Lama presently lives in exile in India, but often visits other countries. Many monks and other religious people also were forced to leave the country, and many of them started Buddhist and Bon centers in cities around the world.

History

changeTibet formed from communities living along the Yarlung Tsangpo, the longest river in Tibet. Namri Songtsen united these communities under one king around 600 CE, with the city of Lhasa becoming capital. His son Songtsen Gampo took control of land beyond Lhasa and the Yarlung Tsangpo and started the Tibetan Empire. Tibetan writers say that Buddhists came to Tibet for the first time while Songtsen Gampo was king. Trisong Detsen, king from 755 to 794 CE, gave a lot of support to Buddhism. He helped build a monastery at Samye, which became very important. During Trisong Detsen's time as king, the Tibetan Empire had control over large areas of land. Tibet's borders touched Central Asia and Afghanistan at the west, Bangladesh at the south, and China at the east. After the king Langdarma was killed in 842, the Tibetan Empire collapsed, and Tibet was no longer united under one king.

In the late 900s and 1000s, people started new Buddhist and Bon traditions. Three of the four schools of Tibetan Buddhism were started during this time, as well as the first Bon monasteries. People who study Tibet's history call this time the Tibetan Renaissance. In 1042, the Indian Buddhist master Atisha came to Tibet. Atisha inspired a reform of Tibet's monasteries and wrote an important guidebook for people to gain enlightenment. These kinds of guidebooks are called lamrim, and all of the lamrim books in Tibet are based on Atisha's book. The largest school of Tibetan Buddhism, the Gelug school, was started by people inspired by Atisha, particularly the monk Tsongkhapa (1357-1419). Tsongkhapa's writings on philosophy became the new norm in Tibet.

The Mongol Empire sent armies to Tibet in 1240, and took control over the country over the next nine years. The Mongols left the running of the country to leaders from the Sakya school of Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhism spread to Mongolia, and today most people in Mongolia are Buddhists as a result. In the mid-1300s, Tibet became independent again, but the Mongols still had some power and influence. In 1577, the Mongol leader Altan Khan gave the leader of the Gelug school the title Dalai Lama. The fifth Dalai Lama was able to gain control of all of Tibet, and the Dalai Lama became not just the leader of the Gelug school but the leader of Tibet as well. During the 1700s, the Qing Empire, based in China, sent armies to Tibet and took official control of Tibet, but the Qing emperors mostly let the Dalai Lama run the country. The Qing emperor Qianlong gave his support to Tibetan Buddhism, allowing new translations of Buddhist books to be made and building new temples. In the late 1800s, the British Empire and Russian Empire began to be interested in having control of Tibet, as it was in the middle of Russian colonies in Central Asia and British colonies in India. Britain sent armies to Tibet in 1903-4. They forced Tibet to agree not to be friendly with Russia. A revolution ended the Qing Empire in 1911, and Tibet became independent again, and was independent for the next thirty-six years.

In 1949, Mao Zedong became the leader of China. Mao and the Chinese leaders thought that China should regain control of Tibet, and in 1950, Chinese troops entered the east of Tibet. Mao Zedong was a communist, and thought that many things about the way Tibetans lived their lives should be different. The Chinese communists did not like how much power the Dalai Lama, the Gelug school, and Buddhist groups in general had over Tibetan society, and they wished to reform how land was owned in Tibet. The changes the Chinese Communist Party made in Tibet were enforced with violence, and Tibetans began to rebel against the Chinese government. The Chinese responded by sending many troops in 1959, forcing the Dalai Lama and thousands of other Tibetans to flee to other countries. The Dalai Lama started a government in exile in India. Between 1959 and 1961, most of Tibet's monasteries were destroyed, and the Chinese Communist Party gained control over Tibetans' lives. China created an administrative division from part of Tibet called the Tibet Autonomous Region in 1965, although ethnic Tibetans have not had much say in the running of this region. The Chinese government has encouraged large numbers of Han Chinese people to settle in Tibet. Groups outside of China such as the Human Rights Watch argue that the Chinese government is oppressing Tibetans and causing them to lose their culture.[6]

Political divisions

changeTibet is divided into 2 municipalities (地级市) and five autonomous prefectures (自治州).

- Lhasa (拉萨)

- Xigaze (日喀则)

- Ngari Prefecture (阿里地区)

- Nagqu Prefecture (那曲地区)

- Chamdo Prefecture (昌都地区)

- Nyingchi Prefecture (林芝地区)

- Lhoka Prefecture (山南地区)

Influence outside Tibet

changeTibetan culture also influences other regions nearby, such as Nepal, Bhutan, parts of eastern Kashmir and some regions in northern most Republic of India, most notably Sikkim, Uttaranchal and Tawang. China claims part of the Indian province of Arunachal Pradesh as South Tibet.

Unrest

changeThere has been some protests in Tibet since China took control in the 1950s.[7] Most of them have been because of social or economic problems. Some of them have been because there are people who believe Tibet should not be a part of China. To show their resistance, many Tibetans set themselves on fire to put the Chinese government under pressure to become independent again. In 2011, 19 people killed themselves.[8] A railway line, the Qingzang railway, has been built, linking China to Lhasa. Also, rising prices of food, and difficult access to higher education have angered many people.[9] The railway line also raised fears about more migration.[10] This situation has led to some violence against people from outside Tibet. Some of this violence occurs outside Tibet.[11] When it comes to assigning government posts in Tibet, more other nationalities of Chinese seem to be assigned, rather than Tibetans.[12] The Chinese Government claims that if Tibet became independent again, its economy would suffer.

Related pages

changeReferences

change- ↑ Wang, Yiyan (2013). "The Politics of Representing Tibet: Alai's Tibetan Native-Place Stories". Modern Chinese Literature and Culture. 25 (1): 96–130. ISSN 1520-9857.

- ↑ Siddiqui, Ataullah (1991). "Muslims of Tibet". The Tibet Journal. 16 (4): 71–85. ISSN 0970-5368.

- ↑ "Journal of Religion and Film". Archived from the original on 2007-01-26. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ↑ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Extreme Unction". www.newadvent.org.

- ↑ "The Tibetan Book of the Dead". Archived from the original on 2007-12-10. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ↑ "China and Tibet". Human Rights Watch.

- ↑ "Tibetan Resistance (Tibet)". www.crwflags.com.

- ↑ LaFraniere, Sharon (5 February 2012). "3 Tibetan Herders Self-Immolate in Anti-Chinese Protest". The New York Times.

- ↑ Tibet, International Campaign for (22 March 2001). "Tibet activists confront Qian Qichen at State Department".

- ↑ Hoh, Erling; Service, Chronicle Foreign (24 February 2005). "Train heads for Tibet, carrying fears of change / Migration, tourism likely to increase". SFGate.

- ↑ "Ethnic unrest continues in China, International Herald Tribune, April 8,2008". Archived from the original on 2008-04-16. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ↑ "Personnel Changes in Lhasa Reveal Preference for Chinese Over Tibetans, Says TIN Report". Archived from the original on 2008-10-11. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

Other websites

change- Tibet Travel Guide

- Tibet Travel Permit

- Tibet Travel Agency Archived 2016-10-31 at the Wayback Machine