Sahelanthropus tchadensis is a fossil hominid. From evidence at the fossil site in Chad in the African Sahel, it is thought to have lived about 7 million years ago.

| Sahelanthropus Temporal range: late Miocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Tribe: | |

| Genus: | Sahelanthropus Brunet et al., 2002

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Sahelanthropus tchadensis Brunet et al., 2002

| |

The split of the line into humans and chimpanzees (known as human-chimpanzee divergence) probably happened between 6.3 and 5.4 million years ago. This can be seen from genetic data.[1] Because the fossil is older than this spilt, its status is unclear. The first fossil found is known as Toumaï today.

Fossils

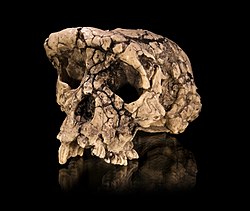

changeSome fossils, a cranium (skull), five pieces of jaw, and some teeth, make up a head that has features that are like both modern and primitive humans. The braincase is only 340 cm³ to 360 cm³ in volume, about the same as chimpanzees. It is much less than the human volume of about 1350 cm³.

The teeth and structure of the face are very different from Homo sapiens. The cranium found is damaged, it is very distorted, so no 3D computer reconstruction has been made. There are no bones other than parts of the skull. It is unknown if Sahelanthropus tchadensis was bipedal (walked on two legs). The placement of the foramen magnum suggests they were, though. Its canine wear is similar to other Miocene apes.

Relationship to modern humans and great apes

changeSahelanthropus may be an ancestor of both humans and chimpanzees; no consensus has been reached yet by the scientific community. The difficulty is caused by its "mosaic of primitive and derived features".[2] Probably it lived in semi-open woodland and savannah, rather than the rainforest of present-day apes.[3]

Another possibility is that Toumaï is related to both humans and chimpanzees, but is the ancestor of neither. Brigitte Senut and Martin Pickford, the discoverers of Orrorin tugenensis, suggested that the features of S. tchadensis are consistent with a female proto-gorilla. Even if this claim is upheld, the find would still be significant, for at present few chimpanzee or gorilla ancestors have been found anywhere in Africa. Thus, if S. tchadensis is an ancestral relative of the chimpanzees (or gorillas), it represents the first known member of their lineage.

Furthermore, S. tchadensis does indicate that the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees is unlikely to resemble chimpanzees very much, as had been previously supposed by some paleontologists.[2][3]

The fauna found at the site suggest an age of more than 6 million years, as these species were probably extinct already by that time.[4]

Possiblility of much earlier split

changeOne study has suggested a much earlier split between the line which led to modern apes, and the line which led to modern humans.[5] The complete mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) molecule of the baboon Papio hamadryas was sequenced and included in a molecular analysis of 24 complete mammalian mtDNAs. The aim of the study was to time the divergence between the Old World monkeys (Cercopithidae) and the Hominoidea. That divergence, at 30 million years ago (mya), was a reference point for the split between chimpanzee, and Homo at 5 mya.

In the later study by Arnason and colleagues, two independent nonprimate molecular references were used.[6] These two references suggested that the Cercopithecoidea/Hominoidea divergence took place >50 mya. Also, all hominoid divergences receive a much earlier dating. Thus, the estimated date of the divergence between Pan (chimpanzee) and Homo is 10–13 mya and that between Gorilla and the Pan/Homo linage approximately 17 mya. The same datings were obtained in an analysis of clocklike evolving genes.

Related pages

changeReferences

change- ↑ "Evolution's human and chimp twist". BBC. May 18, 2006. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Guy F. et al. 2005. Morphological affinities of the Sahelanthropus tchadensis (Late Miocene hominid from Chad) cranium. [1] PDF fulltext Supporting Tables PNAS, 102: 18836-18841.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Wolpoff M.H., et al. 2006. an Ape or the Ape : is the Toumaï cranium TM 266 a Hominid?, PaleoAnthropology, 2006: 36-50.

- ↑ Brunet M. et al. 2005. New material of the earliest hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad. Nature, 434: 752-755

- ↑ Arnason U; Gullberg A.; Janke A. (December 1998). "Molecular timing of primate divergences as estimated by two nonprimate calibration points". J. Mol. Evol. 47 (6): 718–727. Bibcode:1998JMolE..47..718A. doi:10.1007/PL00006431. PMID 9847414. S2CID 22217997.

- ↑ The divergence between artiodactyls and cetaceans at 60 MYBP and that between Equidae and Rhinocerotidae at 50 MYBP

- Brunet, Michel; et al. (2002). "A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa" (PDF). Nature. 418 (6894): 145–151. doi:10.1038/nature00879. PMID 12110880. S2CID 1316969. [2]

- Guy, Franck; et al. (2005). "Morphological affinities of the Sahelanthropus tchadensis (Late Miocene hominid from Chad) cranium". Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. 102 (52): 18836–18841. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10218836G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509564102. PMC 1323204. PMID 16380424.

- Wolpoff, M. H.; et al. (2006). "An ape or the ape: is the Toumaï cranium TM 266 a hominid?" (PDF). PaleoAnthropology. 2006: 36–50.