The Master and Margarita is a novel by Mikhail Bulgakov (1891–1940), a Russian author. It has been called one of the masterpieces of the 20th century.[1][2] Like much of Bulgakov's work, magic realism and fantasy occur against the background of life in the 1920s Soviet Russia.

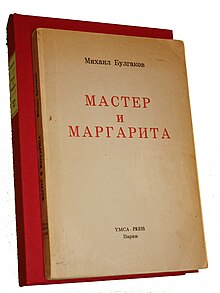

1st book edition, YMCA Press, 1967 | |

| Author | Mikhail Bulgakov |

|---|---|

| Original title | Мастер и Маргарита |

| Country | Soviet Union |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Fantastic, farce, mysticism, romance, satire, Modernist literature |

| Publisher | YMCA Press |

Publication date | 1966–67 (in serial form), 1967 (in single volume), 1973 (uncensored version) |

Published in English | 1967 |

| Media type | Print (hard & paperback) |

| ISBN | 0-14-118014-5 (Penguin paperback) |

| OCLC | 37156277 |

The plot

changeWith a fascinating cast of characters, the novel in its deepest layer is about the interplay of good and evil, innocence and guilt, courage and cowardice.

The novel is a satire on the Soviet society, a love story and an ironical look at some religious themes, all interwoven with elements and characters from the Faust legend.[3] The novel is divided into two parts. It starts with a plot in which two apparently unrelated stories alternate chapter by chapter.

Part one

changeThe first plot theme is the Devil in modern Moscow; the second is the story of Pontius Pilate.

Plot line A

change1930s Moscow is visited by Satan in the guise of "Professor" Woland or Voland (Воланд). This mysterious magician of uncertain origin arrives with a retinue.

- Woland's retinue

- a grotesquely dressed valet Koroviev

- a huge, mischievous, gun-happy, fast-talking black cat Behemoth, a subversive Puss in Boots. The name refers to the Biblical monster and the Russian word for Hippopotamus.

- a fanged hitman Azazello

- the pale-faced Abadonna with a death-inflicting stare

- the witch Hella

The group causes havoc in the literary elite, especially its trade union, MASSOLIT. MASSOLIT is a Soviet-style abbreviation for the "Moscow Association of Writers" or "Literature for the Masses". Targets are Massolit's posh HQ, corrupt social-climbers and their women (wives and mistresses alike), bureaucrats and profiteers and, more generally, skeptical unbelievers in the human spirit.

Plot line B

changeThe second setting is the Jerusalem of Pontius Pilate, described by Woland talking to Berlioz and later echoed in the pages of the Master's novel. It concerns Pontius Pilate's trial of Yeshua Ha-Notsri (Jesus the Nazarene).

- Sympathetic characters

Linking plots A and B are the rather sympathetic characters of Berlioz, Pontius Pilate and Ivan Ponyryov, a young, aspiring poet whose pen name (Bezdomny) means "homeless".

Berlioz is the head of MASSOLIT. Berlioz brushes off Woland's prophecy of his death, only to have it come true just pages later in the novel. Ivan, the young poet "Homeless", tries to chase and capture the gang and warn of their evil. This lands him in a lunatic asylum, where he meets the Master (named Faust in the drafts and margins of the manuscript, but never in the finally published version[4]). Led to despair by the rejection of his novel about Pontius Pilate and Christ, the Master burns his manuscript and turns his back on the "real" world, including his devoted lover, Margarita.

Part two

changeConnecting these two themes are Satan himself, and the Master with his devoted lover Margarita. The Master is an embittered author, whose historical novel about Pontius Pilate had been rejected by the Soviet literary committee MASSOLIT.

Part Two introduces Margarita, the Master's mistress, who refuses to despair of her lover or his work. She is invited to the Devil's midnight ball, where Satan (Woland) offers her the chance to become a witch with supernatural powers. This coincides with the night of Good Friday: the Master's novel also deals with this same spring full moon when Christ's fate is sealed by Pontius Pilate and he is crucified in Jerusalem. All three events in the novel are linked by this.

Margarita enters naked into the realm of night. She flies over the deep forests and rivers of the USSR. She bathes, and returns with Azazello, her escort, to Moscow as the anointed hostess for Satan's great Spring Ball. Standing by his side, she welcomes the dark celebrities of human history as they arrive from Hell.

She survives this ordeal without breaking, and for her pains, Satan offers to grant Margarita her deepest wish. Margarita selflessly chooses to liberate a woman whom she met at the ball. Satan grants her first wish and offers her another, saying the first wish was unrelated to Margarita's own desires. For her second wish, she chooses to liberate the Master and live in poverty-stricken love with him.

The Master and Margarita, for not having lost their faith in humanity, are granted peace but are denied light – that is, they will spend eternity together in a shadowy yet pleasant region, having not earned the glories of Heaven, but not deserving the punishments of Hell. As a parallel to the Master and Margarita's freedom, Pontius Pilate is also released from his eternal punishment.

History of its writing and publication

changeBulgakov started writing the novel in 1928. He burnt the first manuscript of the novel in 1930, seeing no future as a writer in the Soviet Union.[5] The work was restarted in 1931. The second draft was completed in 1936 by which point all the major plot lines of the final version were in place. The third draft was finished in 1937. Bulgakov continued to polish the work, aided by his wife, but was forced to stop work on the fourth version four weeks before his death in 1940.

A censored version (12% of the text removed and still more changed) of the book was first published in Moscow magazine (#11, 1966 and #1, 1967).[6] The text of all the omitted and changed parts, with indications of the places of modification, was published on a samizdat basis. In 1967 the publisher Posev (Frankfurt) printed a version produced with the aid of these inserts.

In the Soviet Union, the first complete version, prepared by Anna Saakyants, was published in 1973, based on the version of the beginning of 1940 proofread by the publisher. In 1989 the last version was prepared by literature expert Lidiya Yanovskaya based on all available manuscripts.[source?]

English translations

changeThere are quite a few published English translations of The Master and Margarita, including:

- Michael Glenny, New York: Harper & Row, 1967; London: Harvill, 1967; with introduction by Simon Franklin, New York: Knopf, 1992; London: Everyman's Library, 1992.

- Diana Burgin and Katherine Tiernan O'Connor, annotations and afterword by Ellendea Proffer, Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1993, 1995; New York: Vintage Books, 1996.

- Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, London: Penguin, 1997. ISBN 0-14-118014-5

- Michael Karpelson, Lulu Press, 2006. ISBN 1-84022-657-9

- Hugh Aplin, One World Classics, 2008. ISBN 978-1-84749-014-8

The early translation by Glenny runs more smoothly than the modern translations. Some Russian-speaking readers consider it to be the only one creating the desired effect, though it may take liberties with the text.[7][8] As an example, Glenny's translations leaves out Bulgakov's "crucial" reference to the devil in Berlioz's thought:

- "I ought to drop everything and run down to Kislovodsk." (Glenny)

- "It's time to throw everything to the devil and go to Kislovodsk." (Burgin, Tiernan O'Connor)

- "It's time to send it all to the devil and go to Kislovodsk." (Pevear, Volokhonsky)

- "To hell with everything, it's time to take that Kislovodsk vacation." (Karpelson)

- "It’s time to let everything go to the devil and be off to Kislovodsk.” (Aplin)

Several literary critics have hailed the Burgin/Tiernan O’Connor translation as the most accurate and complete English translation. There are matching annotations by Bulgakov's biographer, Ellendea Proffer.[9] However, these judgements came before the translation by Pevear and Volokhonsky.

A graphic novel, an adaption by Andrzej Klimowski and Danusia Schejbal, published by Self Made Hero in 2008 provides a fresh visual translation/interpretation.

In other media

changeThe novel has been the basis of films,[10] stage productions,[11][12] opera,[13] ballet,[14] and television versions.[15]

Related pages

changeReferences

change- ↑ Mukherjee, Neel 2008. The Master and Margarita: a graphic novel by Mikhail Bulgakov. The Times, London. [1] Archived 2008-07-18 at the Wayback Machine accessdate=2009-01-19

- ↑ The sword and the shield: the Mitrokhin Archive and the secret history of the KGB

- ↑ Elisabeth Stenbock-Fermor (1969), "Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita and Goethe's Faust", The Slavic and East European Journal, v. 13, n. 3.

- ↑ Лидии Яновской, Творческий путь Михаила Булгакова, p. 283.

- ↑ Neil Cornwell, Nicole Christian (1998). Reference guide to Russian literature. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-884964-10-7.

- ↑ "Master: Russian editions". Archived from the original on 20 January 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ↑ Sarvas, Mark. "The elegant variation: a literary weblog". Retrieved 2006-10-25.

- ↑ Moss, Kevin. "Published English Translations". Archived from the original on 24 October 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-25.

- ↑ Weeks, Laura D. (1996). Master and Margarita: a critical companion. Northwestern University Press. p. 244. ISBN 0-8101-1212-4.

- ↑ Master i Margarita (1994) on IMDb

- ↑ The Cambridge guide to world theatre, edited by Martin Banham (CUP 1988)

- ↑ "OUDS do Bulgakov Website". Archived from the original on 2010-08-06. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- ↑ "Master and Margarita: An opera in two acts and four scenes". AlexanderGradsky.com. Archived from the original on 2013-11-02. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- ↑ "The Master and Margarita – Music – David Avdysh". Masterandmargarita.eu. 14 July 1952.

- ↑ The Master and Margarita (Мастер и Маргарита) is a Russian television production of Telekanal Rossiya, based on the novel The Master and Margarita.